At least the Bank of Amsterdam did not use bitcoin

Readthrough of a BIS paper on a 17th century Dutch stablecoin

BIS: https://www.bis.org/publ/work1065.htm

Summary

An interesting story about the Bank of Amsterdam, a 17th century stablecoin

A two-period model for a ponzi confidence game

Spare no expense or life to stop people from dollarizing

An Interesting Story and More Central Banker Trickery

An interesting BIS paper that escaped me from last year, a few months prior to the liquidity crisis in the US banking sector, discusses the story of the Bank of Amsterdam (1609-1820).

The Bank was a public deposit institution that issued a functional 'fiat' currency and conducted open market operations to balance the value of its scrip relative to underlying circulating coins in use in the market.

I credit the authors with acknowledging that the Bank of Amsterdam was functionally a stablecoin on the Dutch guilder:

The early Bank of Amsterdam resembled what we now know as a “stablecoin” – where account-based money is backed by assets of stable value. Indeed, customers would physically deposit metal coins with the Bank and account balances were recorded in a central ledger. These deposit balances could be transferred to other account holders without cost, or withdrawn for a small fee.

The Bank started in 1609 with a mandate to

‘check all agio (of the current money) and confusion of coin, and to be of use to all persons who are in need of any kind of coin in business’

'Agio' referred to the premium or discount to par that coins circulated with in the market. In this regard, it played the role of a clearinghouse for coin and worked to stabilize the value of its scrip through operations to change the supply of its monetary base of Bank guilders.

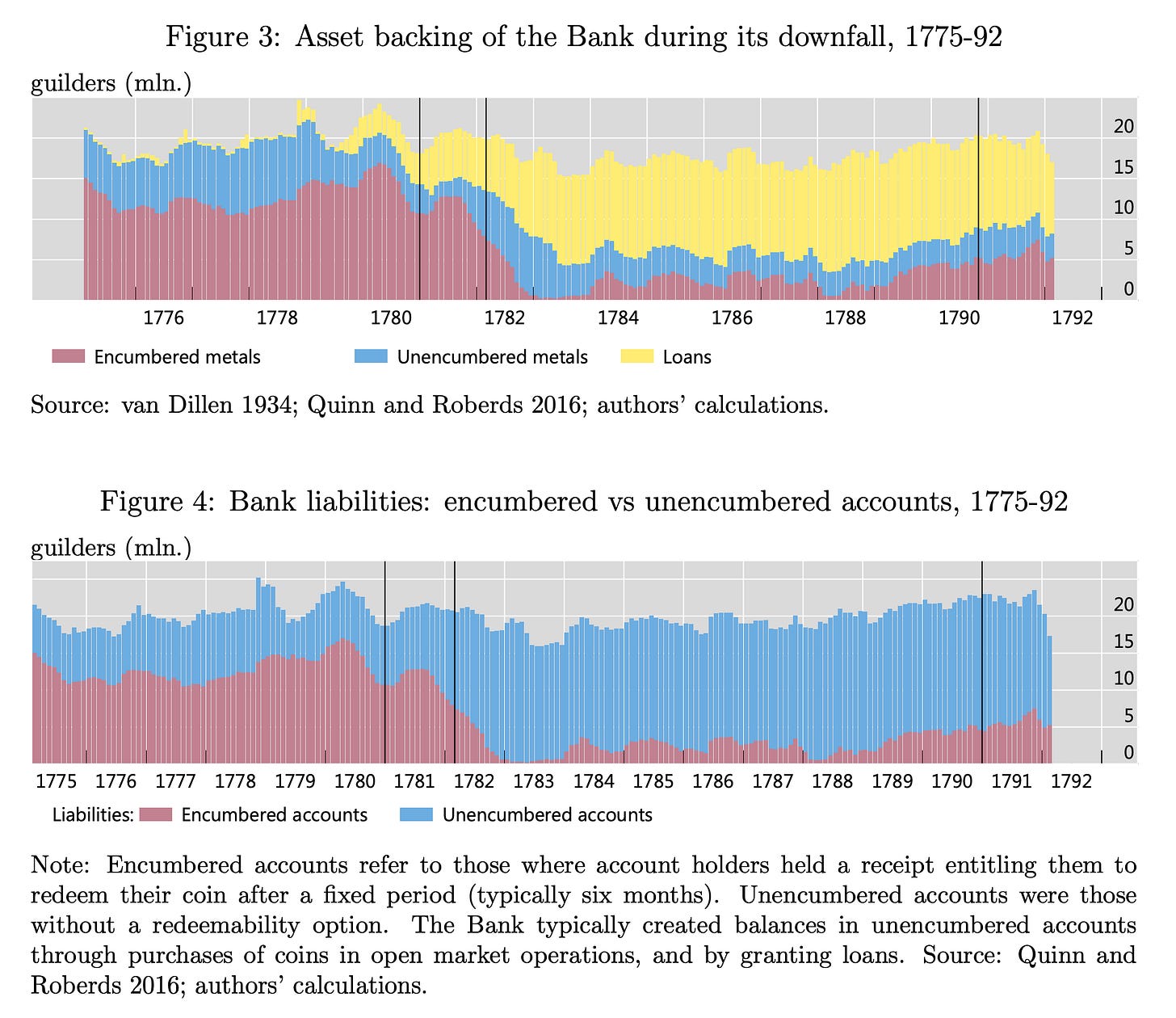

By 1683, the Bank had suspended redeemability of its deposits into coin. It allowed depositors to 'encumber' high quality metal 'trade' coins in exchange for a small interest rate, while retaining redeemability on precious metals. The Bank observed the circulation of 'local' coins closely and targeted a nominal 4-5% premium of Bank guilders.

The Bank's main lending activity was to the Dutch East India Company (VOC), supplying merchant banking capital to trading activities in overseas markets that were a source of precious metals that helped keep the balance sheet of the Bank humming.

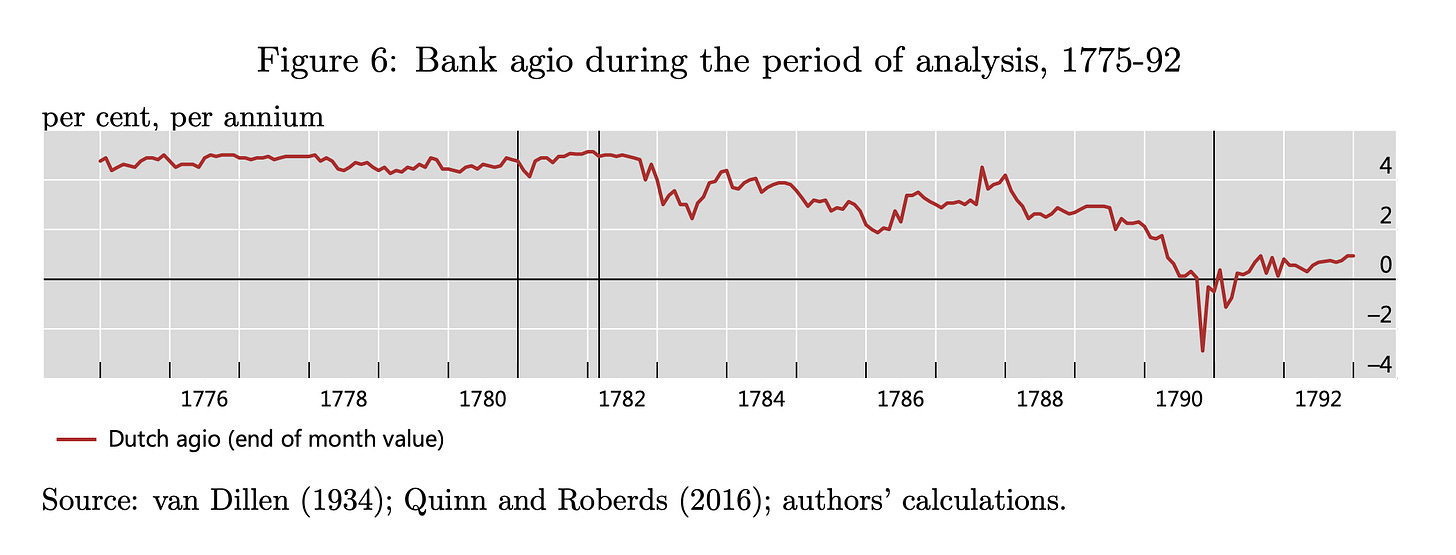

When the Netherlands engaged in wars against England, the Bank stretched its balance sheet to lend to the VOC. By the late 18th century, wars had collapsed trading activity of the VOC and defaults on loans cascaded through to the bank. Metal depositors began to withdraw, eroding the quality of the balance sheet. Opaqueness kept the Bank going through a state of terminal insolvency, though skepticism began to reverberate through the market, pushing the agio, or premium, down to 0% or lower. This dynamic would be exacerbated by counterproductive issuance that the Bank engaged in to support the agio with market operations.

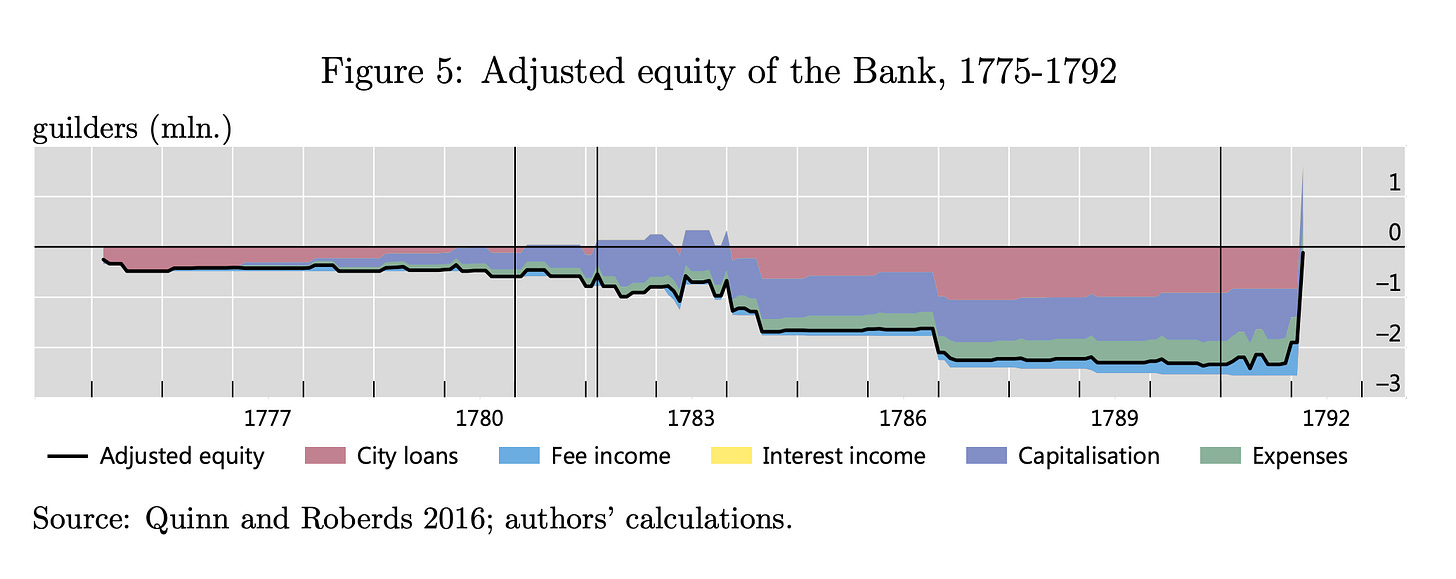

For a brief period the agio went 'negative', or 'depegged' in crypto language. The Bank failed to recapitalize throughout this period and would go as far as distributing profits to government authorities - making the situation worse. It would take occupation by Revolutionary French forces in 1795 to blow the lid open on just how insolvent the bank was as a result of non-performing VOC loans, culminating in its closure.

The paper explores portfolio choice games that merchants face when determining what currency to use, simplified through a first period of imperfect information and a second period when information about the state of the economy is revealed. Through these models, the power of a scrip's network effects is made clear - network effects have value in the context of portfolio choice for a merchant. In the absence of negative perception, network effects make it easy for participants to continue using Bank guilders on the basis that other merchants also use Bank guilders.

Incredibly, the Bank ran at negative equity for a substantial portion of its existence, presumably the 'imperfect information period' that the authors later model.

Though, one must assume that there is some information leakage, given the apparent relationship between the agio (public information) and the depth of the Bank's insolvency (private information).

The ultimate catalyst for the Bank's collapse was the combination of

cratered collapse in network effects or market perception

availability of alternatives that merchants could pick from in their portfolio

reaching the limit of redeemability as all the liquid assets exit the balance sheet, leaving only illiquid (and, in this case, nonperforming) loans

The authors conclude that the lack of fiscal backstops to the solvency of a central bank (or quasi central bank in the case of the Bank of Amsterdam) undermine and exacerbate situations of economic distress. These put pressure on the agio, as a proxy for 'network effects', or desirability to hold Bank guilders.

Reassuringly, one of the conclusions of the authors is that to maintain regimes of 'high trust', central banks need to follow @growing_daniel's exhortations and "do something well".

In practice, there is great uncertainty around where exactly the break point for trust in fiat money would be. Yet given the stakes for the economy as a whole, central banks and governments would do well to stay far clear of this critical threshold.

Worryingly, the relationship to 'fiscal support' is highlighted as a key bastion of ultimate central bank solvency. It's an interesting inversion of the commonly accepted wisdom that central banks function best when they are independent. The original Party line, as I remember it, is that fiscal strength derives from central bank money robustness, rather than the other way around.

Have we always been at war with Oceania? Or is central banking just a Klein bottle, where you have to look at it in four dimensions to understand that central banks and governments fold into themselves indistinguishably?

Our global game model formalises the conditions under which trust in fiat money can evaporate. It shows that there is a unique break point for trust in fiat money, which is more likely to be reached in a severe shock when central bank equity turns deeply negative and fiscal support is lacking. When uncertainty declines, the move from one regime (high trust) to another (breakdown of trust) becomes a step function, and the downfall can be swift and precipitous.

In the paper, the authors thankfully stress that fiscal support needs to come from a government with sound finances, i.e. more tax revenues than expenses. In situations where these hypothetical fiscals have finances that are not sound (there must be some examples, surely), in the absence of reductions in expenses, only one solution presents itself. In these conditions, fiscal support that comes from skinning an already embattled citizenry can hardly be imagined as a source of stability for the financial system.

To some degree, the two-period model presented is a very demure way of describing a ponzi, or a confidence game. In one period, with imperfect information, people have 'confidence' in the game. In the second period, when information is revealed, people rush to the exits. In academic terms:

When uncertainty declines, the move from one regime (high trust) to another (breakdown of trust) becomes a step function, and the downfall can be swift and precipitous.

The authors show that balance sheet 'elasticity' (the confidence game) is supportive for trade expansion and economic growth, and asserts that alternatives must be inferior.

In our model, the agio is the relative price of fiat money versus its alternative, ie coins. The modern day equivalent of the relative price of fiat money differs across countries. For small open and emerging economies, it would often be the US dollar, while new alternatives may arise eg due to “cryptoisation” or the emergence of stablecoins. A shift from fiat money would be visible in quantities and relative prices – especially exchange rates – which become a barometer for trust in fiat money. In line with our model predictions, episodes of dollarisation in past decades show that when this happens, it happens fast. Such a rapid move could be very damaging to the overall economy.

Yet few consumers of dollarization, or even cryptoization, in emerging markets would believe that their economies are worse off as a result of the dollarization. On the contrary, when the confidence game is exhausted and Bank guilders are worthless (cf. Lebanese Pound), dollarization is a lifeline to the economy, rather than a hindrance.

Another, more recent paper, "Is Money Essential? An Experimental Approach" plays games with test subjects to show the presence of money in conditions of monetary equilibrium supports economic expansion. Of course, the paper is written by central bankers, so the phrase actually references 'fiat money'. The real insight is actually that 'any money with network effects and a reasonably stable value in conditions of monetary equilibrium supports economic expansion'. So to the Lebanese exporter, dollars and even bitcoins are preferable to the Lebanese Pound, and merchants that accept both will benefit and produce more.

The paper therefore conceals a statist subtext in a fascinating story about 17th century stablecoins:

Balance sheet 'elasticity' (fiat money) is a confidence game that makes number go up

Sometimes, number go down

This makes fiat money technically insolvent

Technical insolvency is ok as long as people believe in it

If people stop believing in it they might start using bitcoin

This Is Bad because bitcoin does not employ any central bankers

Therefore, the confidence game needs to be kept going as long as possible by being competently run

If it is not competently run, the government needs to backstop with fiscal surplus

(subtext) continues ↓

If the government is not competently run, it will not reduce expenses to raise surplus, but raise taxes

This means generations of citizens will be in a spiraling Road to Serfdom and guaranteed poverty to keep the confidence game going

But this is Okay because at least they will not be using bitcoin