Securitising the Unsecuritisable

Bandwidth trading and echoes of a future past

Bandwidth trading and echoes of a future past

Late 2001 marked, for many reasons, the end of an era and the beginning of a new one. The heyday of outrageous dot-com IPOs and idiotic business models came to a tumultuous end, compounded by one of the most dramatic attacks on American soil ever witnessed.

In December of that year, Enron made its own mark by filing for bankruptcy protection. What had once been a $100 billion titan of American industry and a millenial remnant of the age of power ties, power lunches and power deals, was reduced to petty fraud, the breakup of a venerable accounting firm and jailtime for white collar criminals. Jeffrey Skilling, COO at Enron and an ex-partner at the prestigious consultancy McKinsey, was instrumental in building the Enron empire as well as in perpetrating the most egregious of its financial crimes.

Enron was famous for many things but one of its oft-overlooked calls to fame was the setup of a bandwidth exchange and its participation in it as, essentially, a market-maker in internet bandwidth.

There should be no doubt that the securitisation of commodities such as wheat or soybeans has done much for price stability and guaranteeing liquidity. Instead of having to seek out individual farmers or suppliers, buyers can just go to an exchange and purchase from an undifferentiated seller. Farmers can hedge their payoffs against bad weather with derivatives and buyers can lock-in prices ahead of time with forward contracts. Even electricity can be traded on exchanges, with the added twist that it cannot be stored.

This has been possible entirely for two very basic reasons.

1. Wheat bundled by specification is indistinguishable from another bundle with the same spec

2. The price of wheat on an exchange is completely determined by the interaction of buyers and suppliers

With enough suppliers and buyers, a commodity exchange is as close to conditions of perfect competition as reality allows. But to what extent can bandwidth be treated in the same way?

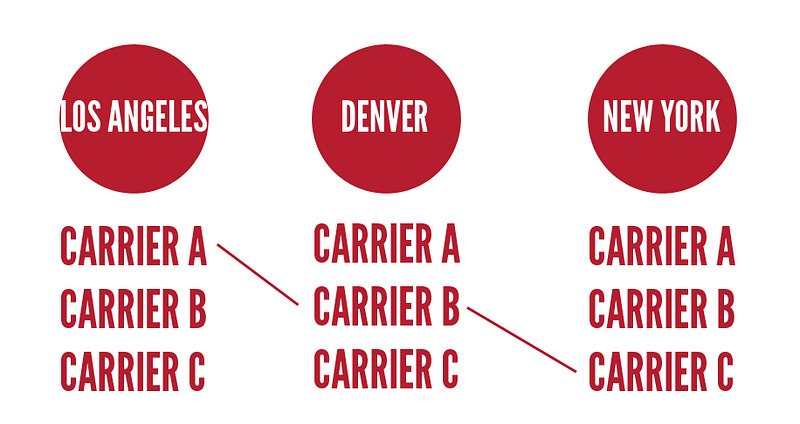

Enron believed it had the answer and set up a bandwidth trading exchange that would prove to be a financial disaster for the company. By pooling together pockets of bandwidth capacity into regional ‘pools’ much like electricity is traded in deregulated markets, Enron was sure it would have the winning formula for a bandwith contract (standardised as city-pair circuits in bits per second for a fixed period of time at a financially guaranteed service level).

The economics of bandwidth trading played against Enron’s assumed role as a market maker, however. With the advent of faster and faster telecommunication networks, Enron’s ‘long’ bet on bandwidth as a market-maker was completely undermined by the widespread availability of cheaper bandwidth. Demand quite simply couldn’t keep up with the immense capacity that was being set up, some of it partly due to the dot com boom.

Enron also discovered that bandwidth wasn’t quite like electricity trading. The advantage of a kWh is that as long as you have a copper wire from your socket to the grid, you can access the deregulated market. However, participants who wanted access to Enron’s pool of bandwidth were forced to set up interconnection systems of their own to a separate bandwidth network. Prohibitively high costs for maintaining individual networks meant that buyers simply continued to establish one-on-one contracts with their existing bandwidth suppliers. Enron’s uncooperativeness and arrogant insistence that consumers and suppliers hook up to its proprietary pooling points made the whole concept of US-wide bandwidth trading absolutely pointless.

Besides, a kWh is a kWh whether it comes from a coal-fired power plant or a solar cell. A unit of bandwidth is much harder to standardise as different networks can only guarantee wildly different levels of service stability or capacity. A financial guarantee of service level was miles ahead of what existing providers offered customers at the time, which was merely a ‘best efforts’ guarantee.

Finally, Enron’s timing was quite simply terrible, set as it was against the backdrop of numerous telecommunications firms fighting to survive and not exactly keen to become bandwidth ‘power plants’, giving up ridiculously gouged revenue based on informational assymmetry with their end-consumers.

But beneath the off-balance sheet transactions and partnerships that have drawn such intense scrutiny, Enron’s efforts to reduce complex products into tradable commodities represented one of the most promising ideas of the past twenty-five years. (Schwartz 2003)

The case of bandwidth trading is as relevant today as it was 13 years ago. There is no doubt that an efficient, international bandwidth trading exchange would do much to reduce internet access prices for consumers and catalyse the end of the long process of commoditisation that internet services have been going through in the past decade.

Any aspiring bandwidth trader would do well to keep in mind the lessons of Enron’s bandwidth business. In 2013 we will witness the growth of cloud-computing exchanges and the introduction of cloud-computing capacity derivatives is not far ahead. There are obvious technical differences between a unit of computing power and a unit of bandwidth capacity. But whether one day you’ll be able to log onto Bloomberg and see a real-time chart for 10TB of month-ahead Amazon Web Services contracts depends on how closely future ‘cloud exchanges’ read up on the adventures of Skilling and Lay.