Steaks and avocados are trade-offs vs solutions

Notes from Thomas Sowell's "A Conflict of Visions"

Would you save 1000 strangers if it meant sacrificing your own child?

Notes on Thomas Sowell’s “A Conflict of Visons”.

Flip the question if you want. Would you save your own child if it meant sacrificing 1000 strangers? In “Conflict of Visions”, Thomas Sowell summarizes a simple difference in worldview, from which a complex chain of consequences on views on society emerge, including on whether your family or the strangers survive.

Despite necessary caveats, it remains an important and remarkable phenomenon that how human nature is conceived at the outset is highly correlated with the whole conception of knowledge, morality, power, time, rationality, war, freedom, and law which defines a social vision.

Coleman Hughes1 summarizes both worldviews, Sowell’s “constrained vision” of mankind and his “unconstrained vision”:

The constrained vision [...] maintains that humans are inherently more flawed than perfectible, more ignorant than knowledgeable, and more prone to selfishness than altruism. Good institutions take the tragic facts of human nature as given and create incentive structures that, without requiring men and women to be saints or geniuses, still lead to socially desirable outcomes

Fundamentally, if you take people “as they are” and you accept that the trade-off of changing them is costlier than simply providing the right incentives for them to behave correctly, you focus on the systems that are necessary to produce good outcomes for everyone. Adam Smith, a moral philospher before he became an economist, would frame it as the need to organize systems that would produce the best possible moral outcomes at the lowest possible psychological cost. The hallmark of people with a “constrained” view is that they focus on trade-offs rather than solutions, and systems over outcomes.

The unconstrained vision, if humans are flawed, selfish, and ignorant, is not due to the unchangeable facts of our nature but to the way that our society happens to be arranged. By reforming our economic system, our education system, our laws, and other institutions, it is possible to change the social world in fundamental ways—including those aspects of it purportedly fixed by human nature.

On the other hand, if you believe people are “perfectible” and can be improved with enough effort, you focus on designing the best possible solution and implementing it regardless of the cost. William Godwin viewed the pursuit of moral perfection as the highest form of virtue, a view which would hold strangers in equal regard as one’s own family as a general utility-maximizer. The hallmark of people with an “unconstrained” view is they focus on solutions rather than trade-offs, and outcomes over systems.

Each view has huge ramifications on how people judge different questions, such as the original “sacrifice your child or a stranger”. If you view utility-maximizing as an imperative, saving 1000 people maximizes utility to far more people than saving one child, even if your own. You might want to avoid situations like it in the future, so you would come up with a complex bureaucracy of state that decides these sorts of problems are “bad” and computes a way to preempt terrorists from putting 1001 people in harm’s way. If you take people as they are, you recognize that self-interested agents will always pick the child and not worry too much about the outcome. To prevent future situations, you might focus on whether you can aggregate a preference for ‘non-1001 people sacrificing’ into a collection of laws and traditions that shun or police such behavior.

While believers in the unconstrained vision seek the special causes of war, poverty, and crime, believers in the constrained vision seek the special causes of peace, wealth, or a law-abiding society.

The collection and transmission of knowledge is another key distinction between each worldview. The constrained view holds that people have hyperlocal, incredibly specialized knowledge in one domain and, being flawed, cannot hope to have a total picture of the whole. But complex societies emerge because the interaction of pockets of knowledge leads to systems and rules that aggregate this information. Knowledge is, therefore, experience collected over time into tradition, where better rules ‘outcompete’ worse ones towards an equilibrium. Treating a flaw in the system as inevitable is not the same as accepting the status quo forever. Many original philosophers with a “constrained” view held anti-slavery positions and advocated for the liberation of colonies for self-government.

Knowledge as conceived in the constrained vision is predominantly experience -transmitted socially in largely inarticulate forms, from prices which indicate costs, scarcities, and preferences, to traditions which evolve from the day-to-day experiences of millions in each generation, winnowing out in Darwinian competition what works from what does not work.

An unconstrained viewholder would conversely prioritize the acquired knowledge of an “educated class” and view anyone not in this class as flawed - though redeemable with enough education. They might produce the reasonable-sounding take that historical tradition doesn’t contain information relevant to organizing the world in the future. Knowledge is derived through reason and handed down from a field of people who have acquired this reason. A flaw in the system is necessarily an output of ‘flawed reasoning’ which can be corrected with enough effort.

Implicit in the unconstrained vision is a profound inequality between the conclusions of “persons of narrow views” and those with “cultivated” minds. From this it follows that progress involves raising the level of the former to that of the latter.

Hopefully some interesting categorizations have already started to occur to you, as they certainly would while reading Sowell’s book. The French Revolution versus the American Revolution, for one, are a contrast between an emphasis on rationality versus acquired tradition respectively. Common Law is the practice of precedents while Napoleonic Law the imposition of rules.

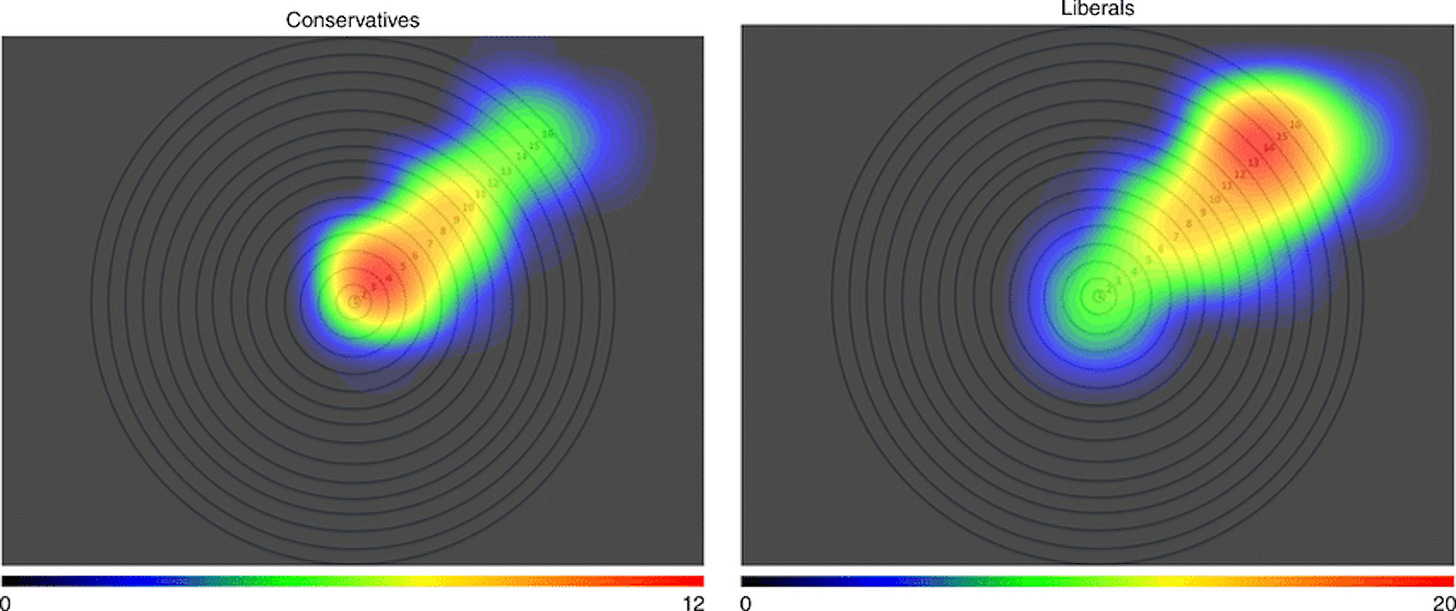

The dichotomy is a simplification and people can be at any point on the spectrum between constrained and unconstrained, just as they can change their minds or switch gears. With this in mind, it’s still one of the clearest frameworks for getting to the crux of a moral argument.

Constrained

View on people: As they are

Progress towards truth: Trade-offs

Unconstrained

View on people: Perfectible

Progress towards truth: One-shots

One wonders if the unconstrained view even existed pre-enlightenment.

Perfect humanity through rationality and out redeem the ultimate redeemer.