You give a value and you receive a value

Trust, long-term games and the insane story of Marc Rich

It's interesting to think about, but commodity trading firms are actually a tremendous and misunderstood force for good in the world.

Short-termism in a corporate context is when managers of a company overvalue meeting short-term quarterly targets over creating long-term value. It's a form of 'present bias', in lay terms (or 'hyperbolic discounting' for insufferable economists).

In 2005, Graham et al1. found that 75% of a sample of 400 CFOs would trade off long-term value for "earnings management". We can take the lazy way out and believe that managers are terrible and that capitalism is poisonous for society, or, instead, look at the incentives and see what people are programmed to want to do.

Quarterly earnings reports are an obligation for U.S. public companies since the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. This was one of many command economy instincts that FDR succumbed to. Like many such distortions, it usually comes from good intentions (preventing another 1929 crash). For more, Martin Daunton’s chapters on the era are highly recommended:

When the state coerces a sampling frequency of 4x a year for disclosures, it becomes immediately clear that managers would solve for them as KPIs over making decisions that are better for the business long-term.

Fewer disclosures are worse for transparency but may allow well-aligned managers to make conscious long-term bets. It would have been interesting to run the experiment of whether the free market would, of its own volition, self-regulate over time towards lowering the risk premium on companies that run their P&L and balance sheets on Dune instead of PDFs. Alas, we are deprived of that possibility, in favor of giant investor relations departments and greater disincentives for private companies to make themselves available to the public as investment opportunities.

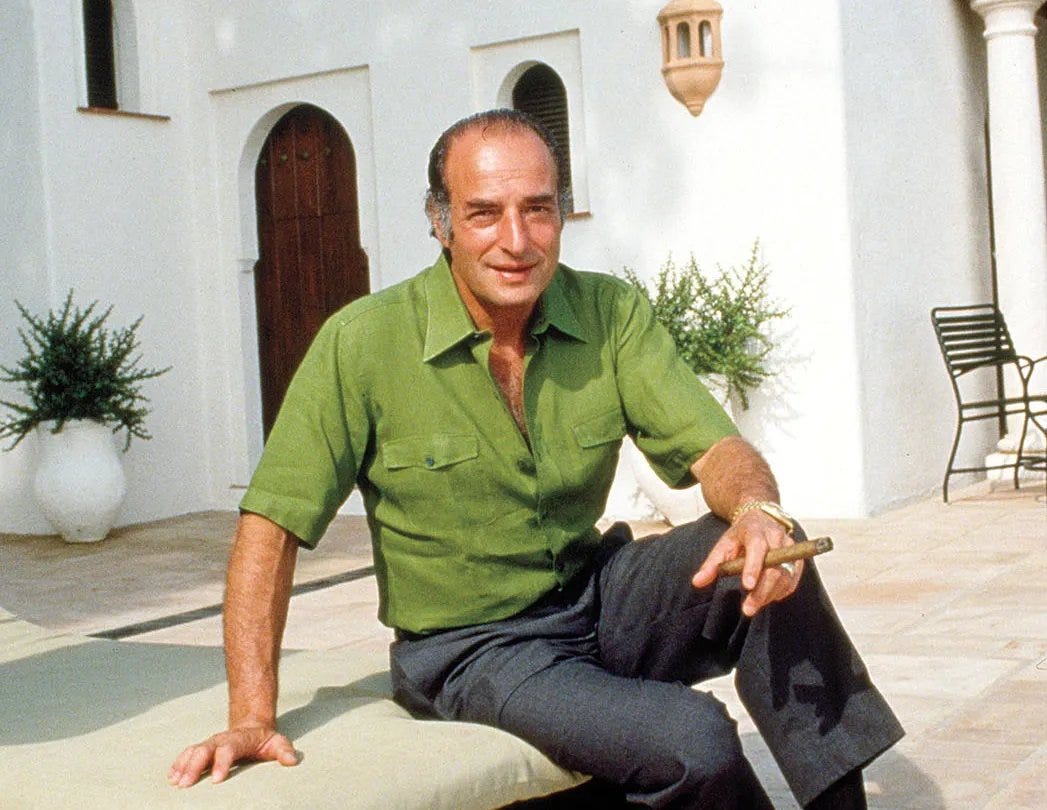

An instructive example of a contrast, a long-term thinker, is the co-founder of the once-upon a time private company Glencore, the artist formerly known as Marc Rich + Co. Daniel Amman, a Swiss business journalist, published in 2010 a tell-all memoir of Marc Rich's insane story in "The King of Oil"2.

It is a riveting book that follows an utterly unimaginable life. Rich was, by all accounts, a 'Live Player'. Samo Burja’s framework of "Live Player / Dead Player"3 explains:

A live player is a person or well-coordinated group of people that can do things differently from how they were approached in the past. That’s pretty rare. Most individuals and institutions are “dead players.” They operate off social scripts handed down from previous generations of experts, superiors and exceptional performers.

Starting his career in the buttoned-up commodity trading firm Philipps Brothers, Rich would push the envelope chasing deals with ambition and a voracious appetite for taking risk. The global oil business used to be controlled by an oligopoly, the "Seven Sisters" (Chevron, Esso, Gulf, Mobil, Texaco, BP, and Shell) who cornered production from insouciant producing countries, often with 1 or 2 year forward agreements at low prices. In 1969, very little oil worldwide traded 'spot'.

Rich's intuition for macro trends helped him understand, early on, that the demand for oil was quickly going to change. He developed, over many years, a web of relationships that allowed him to broker deals outside of the staid and extractive market controlled by the oil majors. By breaking into smaller oil producing regions and connecting buyers with suppliers directly, Rich and his partner Pincus Green blew the doors open and virtually single-handedly created the spot market for crude oil, just as the Six Day War precipitated the 1970s energy crisis and the world's first oil embargo.

The emergence of the spot market would prove to be a transformational development for many countries, particularly in Africa, who had been unable to enter the trade for many years.

The development of freer markets was particularly advantageous for emerging African nations that possessed oil reserves but were unable to extract the oil and bring it to market themselves

Amman's book details many fascinating geopolitical quandaries that Marc Rich was able to successfully navigate, entirely apolitically. From selling Iranian crude oil to Israel, refined Israeli byproducts to Francoist Spain, Cuban crude to Ecuador and the US and back, Marc Rich sat at the intersection of ideologies and focused his company on being of value to his customers. He would prove to be so adept, he found himself navigating even changes of political regime to polar opposite ideologues.

Rich was a mediator who brought together business partners who officially wanted nothing to do with one another. Iran and Israel. Arab states and South Africa. Marxists and capitalists. [...] It is a paradoxical situation that helps illustrate the fact that many of the aspects of the commodities trade are not as they appear. While the Left decries Rich as an exploiter of the third world, it was actually his company that helped ensure the financial survival of the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, who were idealized as 'freedom fighters' by many of the same left-learning people

Rich consciously viewed his business as fundamentally one driven by relationships, which are underpinned by trust. Trust is an important social lubricant and a precondition for a nation's prosperity and competitiveness. Put simply, when people can bank on the idea that other people will follow the rules, transaction costs, search costs and other frictions decline. Productivity follows. With greater productivity, there are more opportunities, prosperity and the tide lifts all boats. To gauge intuitively whether you live in a low vs high trust society, you could run a thought experiment to follow what would happen if you left your wallet on the sidewalk. Now imagine you wanted to sell Angolan crude oil to the United States.

Marc Rich cultivated loyalty and trust to such a high degree that players of virtually any stripe could count on him for a lifeline, even at the height of maximum risk and uncertainty. Where a developing African nation might show a U.S. diplomat the door, Rich might just be at the table, offering valuable assistance and financial support instead. The least satisfying story of Rich is of the unscrupulous vulture. The forbidden question really is, why does diplomacy fail where Marc Rich succeeds?

The spring of 1979 saw the beginning of one of the twentieth century's most astounding business partnerships. Shortly after the revolution, the anti-Semitic, anticapitalist, and anti-American regime of the Ayatollah Khomeini decided to do business with none other than the Jewish American businessman Marc Rich. […] I had asked him how he had managed to gain the trust of the new Khomeini regime, even though he had worked closely with the Shah's government. His laconic answer helps to explain why traders such as Rich exist in the first place, and why they are in such great demand. "We performed a service for them," Rich explains. "We bought the oil, we handled the transport, and we sold it. They couldn't do it themselves, so we were able to do it."

Developing trust is a very long-term strategy that requires constant investment and has little room for straying. Frequently, March Rich + Co traders would forego short-term profits or squeezing clients during a supply crunch in order to maintain credibility for future business.

He did not want to ask for the highest possible price, as that would have contradicted his long-term strategy. "To sell a product at the highest possible price to a client in need is like taking candy from a baby," one of Rich's experienced traders explained the company's philosophy. "We just wanted to make something on top of it all. We knew the customers would be grateful and would someday make it up to us. We were investing in the future. The highest price was not the most important factor. What was important was to build up a stable position and a stable business relationship"

Daniel Amman writes an instructive note, remarking on the contrast between the short-termist incentive of regulated capitalism and the trustworthy commodity trader:

His company is in many ways the antithesis of the fallen business elite that does not seem capable of looking past the next quarter. An era in which oil prices reached new records saw the reemergence of the myth of the commodities trader as a man who could make millions of dollars in seconds with a single telephone call. The reality is something entirely different. The commodities trade is a hard, capital-intensive business with tight margins. [...] Successful traders have to look far ahead into the future. "The key to success - and to real wealth - is long-term thinking," Rich says. Six months in South Africa in order to negotiate the purchase of a mine? Six months in Cuba in order to ensure a loan is paid back? Advance financing of a smelter that will not be completed for years to come? Such actions are nearly unthinkable for listed companies obsessed with quarterly returns.

This upfront investment is risky in terms of opportunity cost and upfront capital investment, but materializes in longer-term higher profits, as the marginal costs decrease with time. From a macro perspective, these investments are beneficial to everyone, as the intermediary that incurs them helps reduce informational asymmetries (what price should I sell my crude oil stock at?), transaction costs (how do I ship my crude oil stock across the Atlantic?) and search costs (who do I sell my crude oil stock to?).

To return to the original assertion: How are commodity trading firms a tremendous and misunderstood force for good in the world?

Marc Rich + Co turned crude oil from oligopolistic inventory into a lever for growth for many developing countries around the world. He mediated between partners in conflict with one another to meet their needs and keep the wheels of civilization turning for the better.

More fundamentally, through investing consciously in long-term games and building trust with people around the world, he helped lower transaction costs for energy, transferred knowledge and technology to places like Jamaica or Angola, and greased the engine of global growth. This engine drives productivity and lifts people out of poverty better than any force we have been able to discover to date.

Excerpt from "The King of Oil" by Daniel Amman, reproduced under fair use for commentary, just because it’s so relevant and also insane:

There was a great sense of nervousness in the Jamaican department of Marc Rich + Co. in Zug on February 10, 1989. The charismatic politician Michael Manley had just been elected prime minister in Kingston. His socialist People’s National Party had won in a landslide, and Rich’s people were prepared for the worst. “We were waiting for Manley’s people to call and tell us to stay in Switzerland and not to come back to Jamaica,” said one of the traders who had feared for his future then. In those days Michael Manley was a hero of the European Left. The former union functionary cultivated an anti-imperialist rhetoric directed against the United States, and he openly admired Communist Cuba as a role model for his nation. One of the main themes of the election was the question of how Jamaica should handle its natural resources. The Caribbean island is one of the world’s largest producers of bauxite, the ore from which aluminum is won. Manley was highly critical of Jamaica’s cooperation with Marc Rich.

Rich owed his reputation to the oil trade, but as we have seen, his company traded commodities from aluminum to zinc. Bauxite, aluminum oxide, and aluminum made up about a fourth of its income. Rich had been represented there for some years by his company Clarendon, which dealt directly with the Jamaican government. Manley’s People’s National Party had promised to stop all business with Rich and to closely reevaluate all existing government contracts with his company. Placards with photomontages were displayed at the party’s rallies depicting Marc Rich with blood on his hands. He was denounced as an archetypical exploiter and “foreign parasite.”

Manley’s first appearance in the Jamaican parliament turned out to be a huge disappointment for Rich’s critics. He had made a mistake concerning “the Marc Rich matter,” Manley admitted during the budget debate of March 1989. His government would “of course” honor Jamaica’s contracts. Rich’s critics around the world—particularly activists in the antiapartheid movement, a movement with which Manley was closely associated—were crestfallen. They had hoped that Manley would promptly turn his back on Rich. Why, they asked themselves, did Manley make such a staggering 180-degree turn?

The simplest answer to this question was given to me by a banker who worked for Rich. “Marc Rich had saved Jamaica. He had bailed it out.” At that time, in spring 1989, officials from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were in Kingston to inspect the government’s bookkeeping, and further IMF credit was dependent on the results of the inspection. The Caribbean island was as reliant on foreign loans as an addict is on his drug of choice. Jamaica was deep in debt, its balance of payments was heavily in the red, and the Jamaican dollar was steadily losing value. In the spring of 1989 it looked as if Jamaica would flunk the inspectors’ test. Most significant, the country maintained lower currency reserves than the amounts stipulated by the IMF, which were intended to help Jamaica meet interest payments and obtain further loans. The new government was lacking $45 million in hard currency, and it needed to find it fast; otherwise the IMF would stop the flow of credit into the country. Jamaica would then find itself unable to meet its payments—a development that would have devastating effects for the Jamaican economy and people.

In the end, even socialist beggars can’t be choosers. Shortly after assuming office, Prime Minister Manley entered into talks with Clarendon’s managers. They explored the idea of Rich helping Jamaica with a loan—and discovered they were preaching to the converted. The IMF forbade countries from borrowing money to cover their currency reserves, so a normal loan was out of the question. Rich’s people, however, believed the problem could be solved with a bit of “creative accounting.” They offered to give Jamaica the desperately needed $45 million, but not as a loan. Instead, the money was intended as an advance payment on future aluminum oxide deliveries. Jamaica was saved; IMF officials accepted the government’s accounts and approved the new credit.

Critics maintain that Rich was thus essentially able to buy Manley and effectively take Jamaica hostage. However, the reality of the situation was that no bank, no international organization, and certainly no other company would have been prepared at that time to lend Jamaica a single cent. The country was over $4 billion in debt and was not even remotely creditworthy. “In any other company it would have been considered crazy to give Jamaica money under such circumstances,” a Rich employee who played an important role in the Jamaican negotiations told me, “but we never let down the people who do business with us. We sometimes even took on losses.” Of course, Rich’s people were not helping Jamaica out of a sense of charity: “For us every situation was an opportunity. We weren’t looking for fast money. We were looking for an ongoing relationship.”

Rich’s companies were willing to accept the smallest of profit margins—and ready to take an occasional temporary loss—in order to break into a market or enlarge their market share. The trade in commodities—and this is particularly true of aluminum—is a cyclical business. A one-or two-year period of high prices can be followed by longer periods of low prices. Those traders who are prepared to operate against the cycle, hold out during dry spells, and even invest during hard times can reap good profits when the prices again begin to rise. There is no better example of this strategy than Rich’s Jamaican aluminum trades.

Rich had already helped Jamaica out of trouble four years prior to the island’s troubles with the IMF. In 1985 aluminum prices had hit a low of $1,080 per metric ton—the lowest price in years. At the same time, oil prices had skyrocketed, making the complicated and energy-intensive production of aluminum even more expensive. The American aluminum producer Alcoa, which mainly made money as a supplier of aluminum to the aircraft and automobile industry, wanted to shut down its Jamaican production facilities for converting bauxite into aluminum oxide due to increasing production costs. It had become cheaper for Alcoa to purchase aluminum oxide from a third party.

The closing of the Alcoa facility was a catastrophe for the country, which lived mainly from tourism and bauxite. It was a golden opportunity for Rich, and his people immediately approached the prime minister, Edward Seaga. “We knew exactly what we wanted. We had a plan that covered everything from A to Z,” Rich’s employee explained. “We told the minister of industry, Hugh Hart, he should suggest to Alcoa that they lease the facility to the government instead of shutting it down. We knew Alcoa would agree, as even a closed facility would have cost them a lot of money. We simultaneously guaranteed Jamaica that we would continue to purchase their yields at fixed prices for a period of ten years. We told the government that we would take care of everything; all they had to do was maintain production.” Clarendon, the Marc Rich company, even supplied Jamaica with cheap oil.

In early 1986 Seaga’s government signed a ten-year contract with Clarendon for the Alcoa facility’s entire annual yield of 750,000 metric tons of aluminum oxide. It was risky for the company to commit itself to a long-term contract while prefinancing the facility’s yield in the midst of a crisis. Metals experts assumed that prices would continue to fall. It was a risk that might pay off only to those who could wait. Marc Rich was someone who knew how to wait.

Two years after Clarendon had signed the ten-year contract at fixed prices, the demand for aluminum began to increase rapidly, and prices began to skyrocket. In 1988 the price for a metric ton of aluminum was at $2,430—more than twice the price at the time of the contract. Rich made a fortune as a result of the simple fact that he had had the patience and the money to wait out the slump in the aluminum market. Jamaica also profited from the rise in prices because the price agreed with Rich was a mix of fixed prices, London Metals Exchange–linked prices, and barter of oil for alumina. Between 1980 and 1990 Rich advanced Jamaica’s government almost $320 million in order to secure annual yields of aluminum oxide. Critics bemoaned the exploitation of the nation’s natural resources by “assorted private individuals.” Rich’s employee in Kingston in those days is of a wholly different opinion: “The Jamaicans are eternally grateful to us,” he told me. “We gave them back their pride, the Alcoa facility was once more able to turn a profit, jobs were saved, and we made a really good deal.”

You give a value and you receive a value.

The Economic Implications of Corporate Financial Reporting, Graham et al (2005), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=491627

The King of Oil, Daniel Amman (2010), https://www.amazon.de/King-Oil-Daniel-Ammann/dp/031265068X